( Click to download the PDF version of this article )

Pathways to resilience

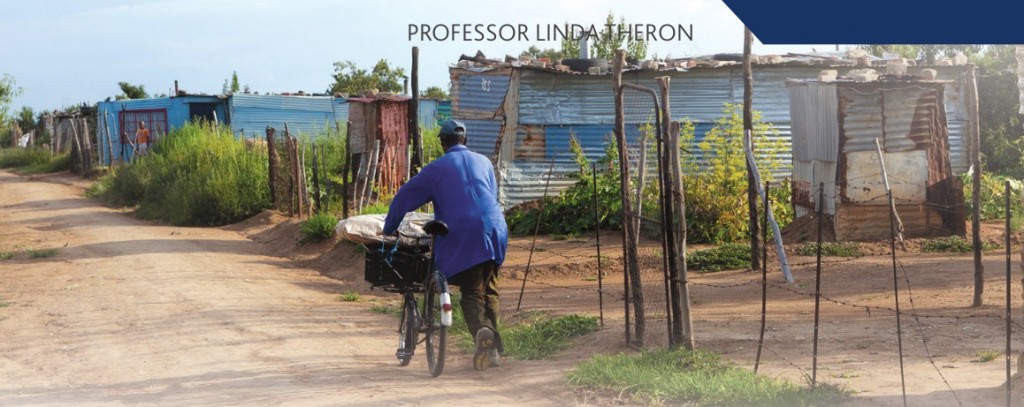

Nelson Mandela once famously said: “There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children”. This mantra has driven Professor Linda Theron in her most recent studies into resilience processes in South African youth

What is your professional background and what attracted you to the study of South African youth?

My professional training is actually in psychology – I am registered with the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) as an educational psychologist. As a young intern in the late 1990s, I gained first-hand insight into the coexistence of strengths alongside vulnerabilities in the South African children I worked with. I was keen to understand why some children drew more deeply on these strengths, thus adjusting well to challenging lives compared with those who remained deeply vulnerable.

Despite growing literature on resilience processes in children, most of this has reported studies conducted with youth in Eurocentric or North American contexts. Given the understanding that sociocultural contexts shape development processes – which include processes of resilience – it was necessary to engage in rigorous research with South African children to truly comprehend their resilience and use this knowledge to support socioculturally congruent resilience processes in vulnerable children.

Can you briefly define resilience? Further to this, what makes the process so complex?

Resilience processes support children to do well in life regardless of adversities that can threaten good outcomes. Resilience processes are informed by strengths in the children themselves (eg. tenacity, a sense of humour, good social skills) but also by constructive relationships with family, peers, teachers, etc. and accessible resources in their communities (eg. effective schools, social services, supportive spiritual practices).

In other words, adjusting well is supported by youth-context interactions and thus, is not a process for which youth can be held accountable. So, to nurture resilience we have to shape the environment around youth to support their resilience, rather than just supporting their strengths.

Perhaps most important is the understanding that youth-context interactions are shaped by the sociocultural contexts of youth. For this reason, processes of resilience will not necessarily be identical across sociocultural contexts. Although the fundamental psychosocial processes might be the same, how the process ‘plays out’ will reflect the child’s sociocultural positioning.

Could you give an insight into the Pathways to Resilience Project?

The Pathways to Resilience Project (led by Professor Dr Michael Ungar, Resilience Research Centre) is a five-country study currently taking place in Canada, China, Colombia, New Zealand and South Africa. Across these varied cultural contexts the aim is to learn which patterns of formal service and informal support work best to mitigate risk and foster wellbeing. We hope to then use this knowledge to influence policy and practice in our communities. In short, the emphasis is on results that are locally relevant.

In South Africa we have paid particular attention to how the sociocultural positioning of young people shapes their resilience processes in order to use this to encourage differentiated services for youth.

How can these pathways to resilience be quantified?

In the Pathways project we made use of mixed methodologies vetted by the Community Advisory Board (CAB) that partnered with university researchers.

We measured the risks faced by our participants, as well as the individual, caregiver and contextual dynamics that support protective youth-context interactions using the Pathways to Resilience Youth Measure (PRYM). We also followed up these quantitative measurements with visual participatory explorations of youths’ resilience to gain deep insight into the socioculturally-shaped pathways of adjustment.

On top of this, the way a child adjusts to challenges at one point in his/her life will not necessarily work throughout his/her life. For this reason, longitudinal studies that include culturally relevant measures of resilience are preferable, and so most of our participants have granted permission for us to contact them in the future in order to understand their adjustment longitudinally.

Finally, in a widespread project such as this collaboration is key. With whom did you partner with and what value did this bring to the project?

My primary collaboration is with the Resilience Research Centre and the researchers partnering in the five-country Pathways to Resilience study. The value of this collaboration is in the multi-cultural lens it brings to the study of positive adjustment and subsequent emphases on the relativity of resilience processes. This collaboration has also promoted the generation of a robust dataset that supports a deep understanding of how young people adjust well to challenging life contexts across the globe.

I also collaborate with NGOs and government departments. Their collaboration is pivotal to the uptake of research results by practitioners and policy makers

~~~

Resilient children of the world

Researchers across the globe are increasingly aware that a one- size-fits-all approach to understanding and promoting resilience processes in impoverished youths just does not fit. Work underway at North-West University is seeking solutions to this challenge

A 2010 STUDY found that of the total estimated 2.2 billion children in the world, around 1 billion – or every second child – currently lives in poverty. Although this figure is shocking, children affected by poverty can sometimes adapt to their adverse situation in a positive way and strive for a better life in later years.

The capacity to adapt in the face of adversity, commonly known as resilience, is the subject of recent and ongoing studies by Professor Linda Theron at the North-West University (NWU) in South Africa. Theron believes her findings can be absorbed into policy and practice initiatives to support resilience processes in impoverished children in her home country and beyond.

DEFINING RESILIENCE

When children fare better than expected given the adversities they face, they are considered resilient. To describe a child as resilient, two key elements are needed. Firstly, a context of adversity must be present, which can be anything from biological or psychosocial threat to experiences of trauma. Multiple or chronic threats are considered more detrimental – poverty is a typical example of compound, chronic risk. Secondly, positive adjustment (or adaptation) – as defined by the child’s sociocultural ecology and commensurate with the child’s developmental phase – to this context of risk must be demonstrated.

Although explanations for positive adaptation in children have been present since the 1970s, they have often focused on Eurocentric populations and this has drawn criticism from researchers across the globe. “To truly understand resilience, we need to embrace its complexity. One way of achieving this is to investigate which ways of adjusting are prioritised by a specific sociocultural ecology, rather than prescribing ways based on studies conducted in alien contexts,” Theron explains.

To counteract this global one-size-fits-all approach, a project called ‘Pathways to Resilience’ was set up in 2009 by Professor Michael Ungar

from the Resilience Research Center, Canada. The aim of the project, which spans five countries including South Africa, is to determine the patterns of children’s formal service and informal support and how these facilitate resilience processes across varied sociocultural contexts.

A SOCIAL ECOLOGY OF RESILIENCE

While there are numerous interpretations of how positive adaptation is affected, the popularity of socioecological transactional explanations is growing. Socioecological transactional explanations of resilience explain positive adjustment as a process of constructive, culturally congruent interactions between children and their environment. In line with this, Theron believes positive adaptation to be dependent on meaningful partnerships between children and their sociocultural ecologies. Accordingly, adjusting well is not a process that

youth can be held accountable for. Put simply, to support children’s resilience, societies need to shape their life-worlds to be more resilience-supporting, rather than only focusing on supporting strengths in youth.

Part of the complexity of a socioecological, transactional explanation of resilience, is that resilience-supporting transactions are likely to differ across contexts and cultures. With this in mind, the Pathways to Resilience team explored patterns of formal service and informal support with a view to deciphering which processes work best to mitigate risk and promote wellbeing, spanning multiple cultural contexts. Theron’s focus was on Sesotho-speaking (Basotho) youths living in the Thabo Mofutsanyana District of the Free State province, South Africa. A team led by Theron engaged 1,209 adolescents aged 14-19 in quantitative and qualitative research.

As in other South African provinces, there are widespread challenges facing youth living in the Free State province. It is thought that around 60 per cent of the youth (especially African youth) live below the poverty line and survive on the monthly equivalent of US $50. Many children are exposed to limited infrastructure; poor service and schooling opportunities; and crime-laden and HIV-challenged communities. On top of this,

more than one third (39.1 per cent) of Free State youth live with their mother only and at least 13 per cent of Free State youth report deceased

fathers. Despite such compound adversity, many of these youth are resilient.

INFORMAL AFRICENTRIC PATHWAYS TO RESILIENCE

To better understand the risks and resilience processes of participating youths Theron and her team gathered quantitative data (n = 1,209) using the Pathways to Resilience Youth Measure (PRYM). To understand both their risk and resilience more deeply, 246 youth agreed to generate qualitative data using focus group interviews and visual participatory methods.

The results of the study show that informal supports are more likely to influence Sesotho- speaking youths’ resilience processes than formal service usage. This means, participants’ positive adjustment to their circumstances of disadvantage is supported mainly by naturally occurring resources found in their families and cultural communities, rather than formal service provision. In particular, attachments to female caregivers (mothers and/ or grandmothers) and to spiritual beings (God and/or ancestors), as well as deep cultural pride predominated explanations of resilience. Of interest is how these informal pathways reflect the Africentric and sociohistorical context in which

participating youth were socialised. For example, an Africentric way-of-being encourages profound respect for inter-dependence and attachment to human and spiritual beings (including ancestors). Given the injustices of Apartheid and associated absences of men from their families, women generally took responsibility for their extended families’ wellbeing.

Regarding the formal pathways to resilience, a path analysis shows that simply providing services to youth is not enough to support positive adaptation. Rather, when service providers and youths form constructive relationships and youth experience the service as being meaningful, the resilience processes surrounding youth are augmented and their functional outcomes (eg. not abusing drugs, remaining engaged in school)

improve. Sadly, the greater the risks faced by youth personally and contextually, the poorer their service use experience.

EDUCATION

“One of the pathways to resilience that South African youth report is educational aspiration, or the profound hope that a good education will potentiate access to university and an upward trajectory thereafter,” Theron reveals. “Sadly though, research on education in South Africa has shown that children from disadvantaged communities typically attend under-resourced schools that offer inferior education, and that fewer than 5 per cent of these students succeed at university level.”

With this in mind, Theron and her colleagues examined the Pathways data to understand when and how schooling experiences support resilience processes in children. Independent sample t-tests highlighted the importance of schooling experiences that are supportive of children’s basic human rights (including opportunities to exercise agency and to be respected), with statistically significantly higher resilience scores than for children who experienced the opposite. Moreover, an analysis of the qualitative data showed that school environments that were rights-orientated had teachers who promoted youth agency, encouraged dreams of continued

education and bright futures, and advocated for safe, nurturing life-worlds for their youth.

WAY FORWARD

Theron has strong beliefs regarding the importance of nourishing childhood development. “If we wish to be known as a society with a healthy soul, then we need to purposefully shape society in culturally relevant ways that nurture children’s positive development,” she elucidates. To do so requires reform in policy and practice. Accordingly, with the support of a Community Advisory Board that has been active in the Pathways project from its outset, Theron and her team are lobbying policy-makers and practitioners to prioritise meaningful relationships with youth, and to draw on and bolster informal supports (such as relationships with women carers and spiritual beings, and cultural pride). They have trained multiple teachers, youth workers, youth leaders, and social workers to support resilience processes in South African children using the Khazimula resilience-supporting strategy – an evidence-based product of the Pathways Project – also accredited as a short learning course by NWU.

The Pathways team, SA, is grateful to IDRC for funding this research. IDRC is not responsible for the contents of this article.

It is thought that around 60 per cent of the youth (especially African youth) live below the poverty line and survive on the monthly equivalent of US $50. Despite this adversity, many of these youth are resilient

INTELLIGENCE

PATHWAYS TO RESILIENCE PROJECT,

SOUTH AFRICA

OBJECTIVES

To understand the formal and informal resilience processes of youth in disadvantaged Africentric contexts, using mixed methodologies and a community-based participatory research approach.

KEY COLLABORATORS

- The Resilience Research Centre (RRC)

- Bethlehem Child and Family Welfare

- Free State Department of Education

- Department of Social Development

- Khulisa Social Solutions

Dr MJ Malindi; Professor AMC Theron, Professor Herman Strydom; Tamlynn Jefferis; Angelique van Rensburg; David Khambule; Divan Bouwer and the rest of the South African Pathways team

FUNDING

International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada

CONTACT

Professor Linda Theron

Optentia Research Focus Area

Faculty of Humanities

North-West University

Office 105, Building 11B

Vanderbijlpark 1911

South Africa

T +2 7169 1030 76

E linda.theron@nwu.ac.za

www.lindatheron.org

www.optentia.co.za

LINDA THERON, DEd is a full professor and experienced educational psychologist. Her research investigates South African youths’ formal and informal processes of resilience, particularly those challenged by poverty. Her research findings inform resilience- supporting interventions. Theron has authored/co-authored multiple related publications. Her post-graduate students explore similar resilience issues. She is also an associate editor for the South African Journal of Education and School Psychology International.

Recent Comments